Migrating data is often a challenging job, especially when every little mistake can instantly impact a user’s experience. Thus, it is necessary to research the task properly, pinpoint possible issues, and make sure the description is totally clear and everyone knows what is the expected result. Nevertheless, errors may (and most probably will) occur during the process so it is also important to keep that in mind and design the solution in a way that anticipates that and handles it accordingly. In the ideal situation, we want to complete the migration process without anyone even noticing that something has changed.

In this post, we will take a look at one of such situations that we have dealt with on one of our projects. The assignment from the manager stood as following: “We need to migrate all user data from MS Azure to AWS”. The reason for that was that we wanted to gradually get rid of technical debt and move everything under one roof and as we already embraced AWS for all our new services, the choice was obvious.

Inspecting the task 🔎

As already mentioned, a properly defined task is a prerequisite for a successful result. Let’s do this now. The project we are migrating data in is a dating app so you could guess there are users’ accounts with each having a couple of nicely looking photos. Additionally, on each photo upload, we generate and store five different versions for performance (large, medium, small) and privacy (if a user doesn’t have active premium) reasons, plus the originally uploaded one. With this approach in place, it might easily happen that one can have dozens of different files associated with the account (not counting other files, such as verifications photos, etc.). Now, that we know what to migrate, let’s make sure we don’t miss any detail.

Designing a solution ✍️

Our solution consists of two main points.

- Start uploading new files to AWS S3 instead of Azure

- Migrate already existing files to AWS S3

Uploading new files to S3

This step is quite simple to achieve. We are using pre-signed URLs for uploading files. This way the API generates a URL which is then read by a client app that then uploads a file directly to a cloud provider via this URL. As a result, the whole uploading process is handled by the cloud provider itself and we don’t have to deal with anything.

Also, it’s important to mention that we use Heroku for running our API which uses so-called dynos which are mortal and so it could easily happen that those instances get restarted when some file is uploading, resulting in a failed upload and lost file. Not good 😬. This is not a problem specific to Heroku, but rather to all cloud providers that run managed applications, therefore you should always strive for designing them to run in a stateless way, so any unexpected restart will not do any damage.

TL;DR: all we need to do in order to redirect all new photos being uploaded to the new location is just change the library (use aws-sdkinstead of azure-storage) for generating these URLs and that’s it.

Migration script

- First, we need to select users for whom we want to migrate data. This sounds simple but some users are already deleted, don’t have any photos uploaded, or have been already migrated, so we want to eliminate those records. Regarding the latter, it’s a good practice to implement a flag column so we know which rows have already been migrated. For this purpose, we added a new column

photos_migrated_at. - Once we have a list of users, we get an array of all stored files and download all of them one by one from the original storage.

- Next, we upload those downloaded files to the new location, in our case AWS S3.

Note, that we used Node.js’s Streams which is much more memory efficient as we don’t need to save the whole file before the actual upload can start.

- Once we have all files uploaded to the new location, the last step is to update the database to point to those new URLs. This is as simple as one SQL update query. In our situation, we also needed to update Firebase, so this means one extra call.

After writing down all the steps this is a simplified version of the migration script. We loop through all the users in batches (pagination) and process files for each given user if they have any URLs to migrate (note that we also check if a file is already stored in S3 before trying to migrate it — isAWSUrl()).

This code works fine but there is one issue. Remember when we said that for each photo we actually need to store five different files? Now, if you look at the code you may notice that we try to migrate all of them asynchronously at once using Promise.all. Imagine that a user has 10 photos, so if we were to migrate all of them simultaneously it would have created 50 pending promises(!). This could get even worse if we decided to migrate all of the users in the current batch asynchronously as well (now we use a for-of loop which makes the processing synchronous).

The more pending promises the more memory used and open network calls which is not good for migration on such a big scale. We can mitigate this by limiting the max allowed number of spawned promises at once by a simple helper function, where we combine synchronous and asynchronous approach by splitting an array into smaller chunks, iterating through them synchronously, and runningPromise.all only on those smaller parts.

This way a code will inherently take more time to complete but will be much more efficient. It is a tradeoff here, and you always have to decide what works better in your situation and what is more important to you — time or resources.

Note: As I learned later, there is something very similar to what we came up with already implemented in the popular library Bluebird.

Launching the migration

As we use Heroku, the easiest and most straightforward method is to run a new separate process. This is as easy as adding a new line to your Procfile.

data-migration: node ./scripts/migrate-user-files.js

Cool, the migration script is running, after a few checks to verify everything works as expected we can finally relax, enjoy our cup of coffee ☕️ and watch how the database is slowly populating with the updated records.

If you are thinking that sounds too easy, you are right. When I said “slowly populating” I had not really thought how slow it could actually be. After running the script for a whole day we ran some statistics queries and quickly realized the script wasn’t performing well. We found out it was processing only about ~700 profiles per hour which after doing simple math meant that it would have needed to run for several months (!!!) to process all the data. This was run on Heroku standard-1x dyno with 512MB of RAM and a price of $25/month. We decided to try it with a larger instance standard-2x that offers 1GB of RAM while paying $50/month. After upgrading the instance and running the script for another day we saw a slight improvement in terms of numbers, but it still wasn’t good enough.

Rethinking the solution 🤔

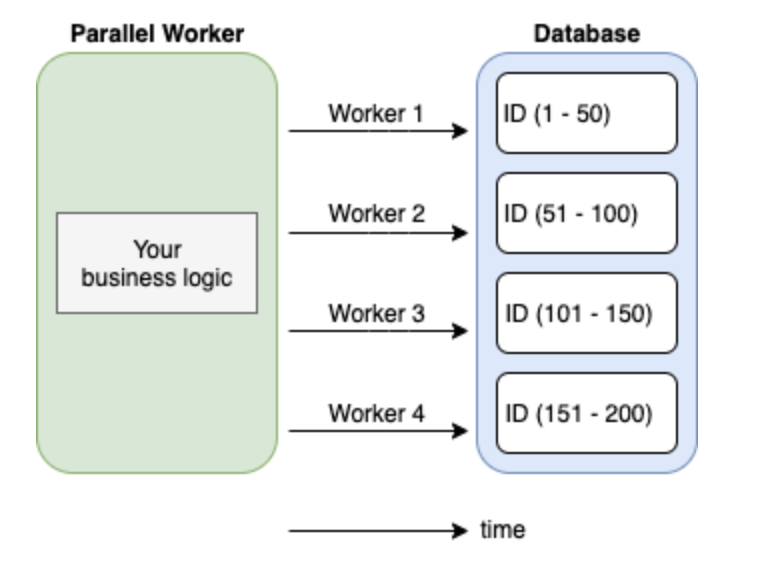

At this point, we knew we had to revise our solution and come up with a more performant alternative. If one process can handle 100 users, two workers should process twice as much, right? With that idea, we decided to run multiple workers in parallel. But now it gets much more complex as we need a way to make sure multiple parallel processes don’t touch the same portion of data.

The plan we came up with consisted of one master and several worker processes_._ For spawning multiple worker processes we used Node.js’s cluster. The job of the master process is to spawn worker processes and then listen for their requests to fetch a batch of data. The master then queries the database in a lock, which assures only one request at a time will be handled, and this way we avoid multiple workers getting the same data. Once the workers get the batch of data they start processing it asynchronously. Anytime a worker is done, it just asks for the next payload.

With this change, the script was able to process roughly 4000 profiles an hour. Yay, this looked very promising 🎉. But only until you do the math again and still don’t get satisfying numbers. It would have still required a couple of months to finish. Since we had the script ready for parallel processing, the next step was to just take bigger advantage of it and try to scale it more 🚀.

Bye Heroku. Hello AWS again 👋

As we could see, Heroku is not very generous when it comes to scaling options and money. We didn’t want to pay this absurd amount of money for even more ridiculous offers (I mean 512MB for 25 bucks? Come on, it’s 2020 already!)

That’s why we decided to run an EC2 instance in the AWS cloud instead. We opted for t2.mediumwith 4GB of RAM for the price of ~$33/month ($0.0464/hour). We increased the number of workers to 6. After running it for another day we were astonished. In this configuration, we were able to process almost 25k of profiles within an hour (😱). Woah, this is something we were looking for. The whole script didn’t even reach half of the available memory so theoretically, we could have tried to add even more workers, but we were happy enough with the current solution and the speed.

Another idea was to enable the so-called VPC endpoint for S3 which allows routing all the traffic between EC2 instances and S3 storage within the internal AWS network, without the need to hit the public internet. This would obviously help to reduce the total time even more, but as I said, we didn’t need any further optimizations.

Orchestrating parallel processing ⚙️

Introducing parallel processing saved us a lot of time and sped things up significantly but also brought more complexity into the code. While developing the solution we found it to be useful in other places or similar situations as well, that’s why we eventually decided to offload the logic into a standalone open-source npm package.

The package works on the idea of master and worker processes and takes care of a few other useful concepts such as retries, dead-letter queues, or exited processes.

How it works

Coming from a real-world scenario this tiny library allows you to process lots of data much faster by introducing parallelism. It spawns multiple workers which access an assigned portion of data in the database simultaneously, so you can process much more data at the same time without worrying about synchronization or duplicate processing.

Using the package is as easy as defining two functions.

setFetchNext(async lastId => { ... })

This function defines the way of fetching the next payload from a database. You provide a callback function as a parameter where you can specify how to fetch data. It is always called just once at a time to make sure it won’t return the same portion of data multiple times which would mean duplicate processing. It gives you a parameter lastIdwhich can be thought of as a pointer for the next database fetch.

setHandler(async ({ lastId, ...payload }) => { ... })

The second function you need to provide is used for specifying your business logic for processing an assigned range of data from a database. You always operate on data in a variablepayload which gives you secure access to the reserved data portion in the database and makes sure no one else will touch this.

Now, when we know how the library is used, here is a rewritten example of the code above:

Summary 👨🎓

The whole process of migration from the initial idea until the last migrated user lasted nearly two months. During this time we defined what was necessary to do, how we wanted to tackle it, and designed the first draft. Quite quickly we encountered some bugs or edge-cases for which the script didn’t operate properly so further fixing and polishing was required. We learned that Heroku is a very good choice for getting started quickly and without much of a configuration but this comes with a significant drawback when it comes to scaling or further development as your hands are tied tightly and you don’t have much control. It’s important to keep that in mind and switch to something more appropriate which gives you better control (e.g. AWS, GCP, …) as soon as your project starts growing.

We had to deal with a kind of “big data” (even though not really) where the original idea might not be always a good fit and you need to take into account the amount of data you need to process. What works well for 10s, 100s or 1000s of users(rows, data, basically whatever) might naturally not work the same way for millions.

Also, on such a big scale errors are more likely to happen and you can never avoid them fully, but you can design your code in a way that embraces it and acts accordingly. As already stated, you can implement retry mechanisms, which should be able to repeat the failed task, dead-letter queues, for keeping the track of erroneous tasks, handling unexpected exits gracefully, so you won’t lose data, etc.

Bonus tip

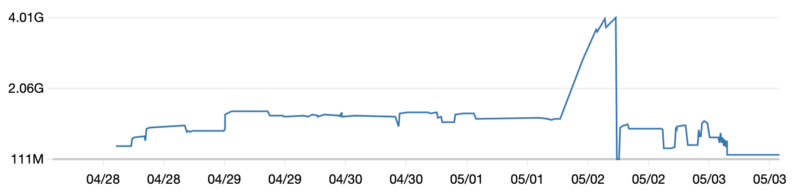

If you read it all up until here, I really appreciate it and here you are one extra bonus tip that we learned the hard way. If you use pm2 process manager, be aware it stores logs by default. It might sound like something obvious but it didn’t to us and therefore we ended up in a situation like this.

As you can see when the script was running normally it used around 2GB of memory but then one day all of a sudden this big spike occurred. After a little bit of investigation, we learned that pm2 stores all the logs on a disk which after a few days resulted in draining all the memory on the instance 😅. The solution was to just delete those logs and add a configuration option to not save anything 😇. After fixing this the script continued working perfectly until everything got migrated.

PS.: All these drops and raises indicate worker processes being killed and respawned respectively.

Further reading

- Upload files using pre-signed URLs

- Heroku dynos

- Heroku Procfile

- Stateless app design

- Node.js streams

- Node.js cluster

- Promises concurrency

- AWS EC2

- VPC endpoint for S3

- ParallelWorker package

- PM2 process manager

- Dead-letter queue

If you liked what you’ve just read don’t forget to give it a clap and I’ll be more than happy to hear your feedback ❤️